The Real Reason Your Good Ideas Fail: Poor Feedback

Improve ideas in your workplace with these crucial feedback tips and tools

Are you struggling to produce good ideas at work? If so, you’re not alone. When I ask this question in workshops or during workplace training's, the collective response is yes. The good news, however, is you don't lack the creativity to conjure up good ideas. No, the real reason your ideas fail to become good is because of poor feedback.

Noted cartoonist Ashleigh Brilliant once said,

“Good ideas are common – what’s uncommon are people who’ll work hard enough to bring them about.”

Part of working hard is giving and receiving good feedback. Unfortunately, your feedback and that of your colleagues is almost always terrible.

Why is our feedback so poor?

Our feedback is poor for a variety of reasons. The biggest is that we are hardwired for the negative. We’ve evolved over thousands of years, keeping a close look out for things that might kill or hurt us. That evolutionary focus on the negative (negativity bias) ensures we identify what is wrong. Unfortunately, we don’t often articulate what is right and good, and furthermore, how to make those things better. If we want our ideas to become good ideas, then one of our goals should be to give good feedback. There are additional approaches to transforming your ideas into good ideas – which I’ll cover in later blog posts – for now, let’s focus on feedback.

How to give good feedback?

To give good feedback, it’s best to concentrate on 2 approaches:

Give specific and actionable feedback.

Just about any book on management or training will give you the same guidance. In practice, however, people given this advice still respond with vague and generally dreadful feedback. That’s because they often don’t have experience or practice giving specific and actionable advice. Make it simple and easy by using the following quad chart to capture feedback.

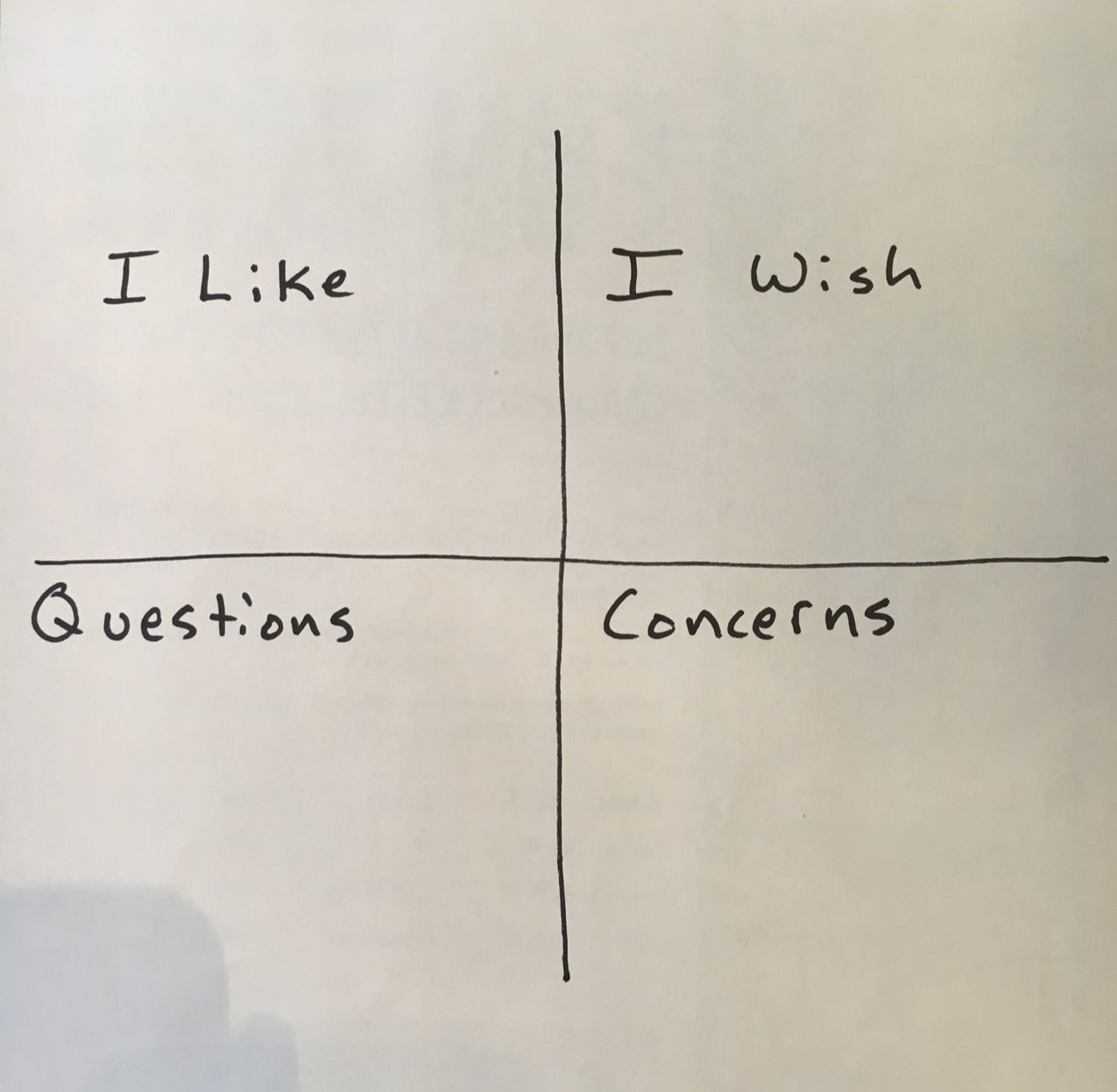

Quad Chart Feedback Tool

The great advantage of using this feedback tool is that it provides a cognitive template (i.e. similar to Mad Libs) that drives the feedback to something that is both specific and actionable. To better understand the tool, here is a description of the individual quadrants in this quad chart. Following these descriptions, I’ll offer practical advice on how you might use this feedback tool (e.g. tips I’ve developed from my experiences).

I Like – This quadrant captures what I Like about the idea.

I Wish – This quadrant captures what I Wish about the idea. You can think of this quadrant as ideas for improvement.

Questions – This quadrant captures questions to help me better understand the idea. These can be clarifying questions, context-gathering questions, technical or non-technical questions – basically any question that helps you gain a better understanding.

Concerns – This quadrant captures any concerns you might have about the idea. Depending on your domain or problem space, this can cover a wide range. For example, you might have concerns about the safety of implementing the idea, or maybe you have concerns about the business viability, or concerns about how quickly you can operationalize the idea.

Tips On Using the Quad Chart Feedback Tool

When it is time for feedback, it is important that you ask your colleagues or feedback participants to capture their critique on post-it notes with one feedback item per post-it note. There are a few reasons for this approach. First, a post-it note is limited in size (typically 3x5 or 2x2 inches). That space limitation forces the person giving feedback to cut out the superfluous and focus on the most important considerations. Second, it minimizes the desire to preamble. Often, people giving feedback preface their response with a long explanation. Doing so limits the amount of feedback from others. Third, it captures the feedback concretely for further review and reflection at a later time.

Give Feedback with Radical Candor

The phrase “radical candor” has been popularized by Kim Scott – an accomplished director at several big Silicon Valley firms over the years. Basically, giving feedback with radical candor comes down to two different questions: how much do you care about someone and how much are you willing to piss them off. If you care about someone, then it’s your moral obligation to challenge and push that person as much as possible. That uncomfortable space is where ideas grow and develop into something great.

Often times, however, we’re afraid of offending our colleagues when giving feedback. Consequently, we tend to water down our feedback or to preface it with qualifiers such as “from my perspective,” or “this is just one viewpoint.” To help you give radically candid feedback, remember the acronym HHIPP, and try using it’s framework. That is, your feedback should be humble, helpful, immediate, private if it is criticism, and public if it is praise (HHIPP). A note of advice – it’s always a great idea to set expectations with your colleagues about feedback by asking them what it is they want to accomplish, or to confirm if they even want feedback. This is beneficial for both sides because they may have specific goals related to professional improvement. Or, on the other side, they may not even desire feedback.

Remember, if you want to transform your good idea to into something great and tangible, seek out good feedback. Similarly, if you want to help your colleagues develop great ideas, remember to give good feedback – be it with a quad chart feedback tool or by embracing radically candid feedback.

3 Ways To Turbo-charge Your Creativity

Summon your creativity in the workplace using these 3 principles of Improv.

Hitting a wall with your creativity at work? Feel like you never generate new or novel ideas? Before you give up and claim you aren’t the creative type – try using these three principles of improv to unleash your creative powers.

1) Develop a Yes And attitude.

The core building block of improv is cultivating a Yes And approach, where you affirm and build on the ideas of others. On stage, this means accepting whatever your scene partner offers you as reality and crafting a reaction, a character choice, or emotion that your partner can use to create a humorous story.

I remember a particularly unforgettable scene where I was asked to play an expert ballet instructor. At that moment, part of me wanted to run off the stage since I didn’t know the first thing about ballet. But the other part of me remembered the Yes And principle, and so I proceeded to craft my character as someone with a background as a US Marine Corp drill instructor. The audience laughed heartily while my Rambo-style ballet instructor barked out calisthenics orders to a group of seasoned ballet dancers.

If you want to cultivate creativity in your professional life, you should consider approaching your work with a similar mindset. Think of your interactions with coworkers as endless opportunities to affirm and build on ideas. This idea sounds easy enough but often you may find it difficult to achieve. It’s much easier to engage in what I like to call Idea-Shooting: when someone tosses out a good idea, you shoot it down. It’s easy to tell a person why the idea is terrible or why it won’t work. But I promise you, if you can table that desire to give critical feedback and keep an open mind instead, your creativity will flow much easier.

Practical Tips:

I find it helpful to practice a Yes And approach to work by using it as a sentence starter in brainstorming, decision making, and other interactions with colleagues. I like to preface my responses with Yes And before responding or interjecting. It sounds somewhat mechanical, but the grammatical structure and logic behind these two little words will force your brain to respond by affirming and building on an idea. The additional bonus of verbalizing Yes And out loud is that it encourages your colleagues to respond in kind and become more open and generative to the ideas of others.

2) Listen Hard.

A second essential improv skill is the ability to listen hard. It’s a funny way to describe the skill, but very appropriate. Almost all of us listen to others with the intent to formulate a response, and not with the intent to understand. When we don’t listen to understand, we short circuit any creativity and generative idea building immediately.

For instance, my scene partner once gave me the gift of playing an astronaut who was afraid of heights. I locked in on playing the role of an astronaut and either missed or ignored the truly juicy and ironic piece involving a fear of heights. When I attempted to progress the scene by highlighting my lack of technical knowledge regarding space shuttles, the scene fell flat because the audience was waiting to hear how I would build my fear of heights into the improvisation. Had I been listening hard, I could have delivered on that expectation, but instead I was listening with the intent to respond and not to understand.

The story is remarkably similar in the workplace, for all of us. If you don’t believe me, go ahead and try this exercise at your next office meeting, review, or conference call: count how many times you can catch yourself thinking about how you’d respond to a colleague as he or she is speaking. The number will surely shock you, even more so when you realize that every one of these instances is a missed opportunity to understand and build on an idea – to make it better, and to innovate.

Practical Tips

Listening Hard might seem daunting, but improving this skill is easy enough with two exercises. The first is to train your brain to be more mindful and to live in the present. Mindfulness meditation is a great way to achieve this, and is, in some sense, the perfect analog to Listening Hard. The idea is to focus your attention on the present moment, without regard for future or past. Thinking about how you would respond to someone as they are speaking is inherently future-oriented. Thus, as you practice mindfulness meditation, you can begin to connect this practice to your daily interactions with your colleagues. If you’re unsure how to start mindfulness meditation, try the guided meditations of Jon Kabat-Zinn – one of the leading voices and pioneers in the field. Several good introductory meditations can be found here and here.

The second way is to practice visual note-taking. Try to focus your brain on the present by visualizing the ideas, details, and intent of your colleagues’ proposals.. Visualizing your understanding of ideas is one of the best ways to learn and remember new or different ideas. Worried about not being an artist and unable to draw well? Set those worries aside. Anyone can doodle, and according to Dan Roam, if you can draw three basic shapes – the square, circle, and triangle – you can draw anything.

3) Erase Self Judgment and Censoring.

Perhaps the most difficult skill of Improv to master is to erase self judgment and censoring. We are social creatures who crave the acceptance of others, so it shouldn’t be a surprise that self judgment and censoring is a ubiquitous trait in all of us. In improv, the skill of avoiding self judgment and censoring is called immediacy, where you are taught to blurt out anything that pops in your mind. When I first started taking improv classes, this was incredibly difficult. I thought I had to be witty, clever, and funny all at once. I’d start analyzing a response or gift on stage even before I spoke it.

In professional lives, we all over analyze our own ideas, opinions, and comments, leading us to shut down valuable contributions to group meetings, brainstorms and other activities. As a result, a great idea is snuffed out before it is even born. It’s important to realize that everyone feels this way about their own ideas at one time or another. The key is to embrace the idea that creating something new and innovative is hard and that most ideas will fall short on their own inevitably. Don’t expect the idea(s) you offer to be amazingly creative right out of the gate. Understand that you are doing the group a great service by putting your ideas out there, no matter what.

Practical Tips

A really fun and great way to improve your skill of immediacy is to play PowerPoint Karaoke with your coworkers on a regular basis. It will help you become comfortable with being uncomfortable as the game forces you to offer ideas on the spot, whether you want to or not.

In PowerPoint karaoke, someone selects a random compilation of images from the web (try using Google’s Image Search Tool). Each person is given three slides with a random image on each slide and 90 seconds (30 seconds per slide) to speak. After 30 seconds, the facilitator automatically moves to the next slide. The speaker’s job is to say something impromptu that stiches together a narrative about the image during the allotted 30 seconds. To spice this activity up, try different formats, time durations and other tweaks to make it more, or less, difficult.

Most people find it terribly uncomfortable at first – myself included. But with practice, it becomes easier, largely because you learn to accept that you do have good ideas and that they don’t have to be perfect. You realize that an idea is just that… an idea. You have a million of them, and you’re comfortable offering them up to your peers without judgment.

Go forth and be creative. Embrace these 3 principles of improv and unleash your creative powers.